This post was adapted from four essays in the author’s monthly poetry craft newsletter, lullabies & alarms.

After sketching out a poem, the next steps can feel daunting. In this post I’ll share 6 steps I usually take when revising my poems, with hopes they will help make the process more fun and more rewarding. (And don’t worry about the order—revision is more a dance than a walk!)

1. Identify the thesis

I define the thesis of a poem as its essential message, or its basic reason for existing.

If you’re not sure what the thesis of your poem is, here are a few creative approaches for identifying it:

Listen—to your heart, your body. What did you feel emotionally and physically when you wrote this poem?

Look—for happy accidents. A moment of sonic assonance, an intriguing phrase, a particular idea or mood that shines through.

Translate—to another art form, even if just hypothetically. If the poem was a sound, what would that sound be? If the poem was a painting, what would it look like? If it was a dance, what would be its signature move?

Translate—to another art form, even if just hypothetically. If the poem was a sound, what would that sound be? If the poem was a painting, what would it look like? If it was a dance, what would be its signature move?

Bounce—the poem off someone else. Ask someone to tell you what they think its essential message is. Their answer might feel good, and you’ll think, Eureka! Or it might feel frustrating, and you’ll think, No! That’s not it at all! It’s ______! And you’ll fill in the blank, and voila—clarity through contrast.

The main goal here is to become clear with yourself about what you’re trying to say or express in a poem, so that when you revise it, you’re as well-equipped as possible to support that expression, whether directly or indirectly.

2. Identify where the poem begins

Sometimes in our first drafts, we write into a poem—we put pen to paper in order to get somewhere that seems poem-ish. That “somewhere” is usually the point at which the poem begins.

What we write before that point is often warm-up text, or has more to do with self-soothing or self-reflection than with the poem itself. When revising, it’s helpful to decide whether you’d like to either include such reflective parts, or treat them as byproducts of the writing process.

Your personal poetic style and aesthetics, the goal(s) of the poem, and its audience all have a lot to do with your decisions around this. Still, I believe every writer can ask themselves the same question:

In this first draft, what did I write for the poem, and what did I write for other purposes?

3. Show & tell strategically

In the visual art world, you might paint a silhouette of a person, or you might paint the areas of the canvas where the person’s silhouette isn’t—but either way, an image of a person will come through. This is the concept of positive and negative space.

In poetry, I’d call this being roundabout vs. straightforward (often referred to as showing vs. telling).

For example, to describe a thing, you could be very straightforward:

In her office

a red flower

dead

in a vase

Or you could be more roundabout, and talk around the thing you’re describing:

a stiff, dead reminder of her

stalked—still—the empty room

pieces fluttered

dryly down

Writing in a straightforward way (or “telling”), is an excellent tool used by many exquisite, badass poems. Writing in a roundabout way (“showing”) is an excellent tool used by many exquisite, badass poems. They’re equally useful tools. So when revising, simply determine which tool might best serve each description, message, and idea.

4. Be consistent

In your poem about love, do you reference soda, pigs, tumbleweeds, and make-up? Can you wrestle those into plausibly being from the same “world”? A poem can often be strengthened by having all its imagery and metaphors be related somehow, however distantly. Endeavor to streamline your references to be all part of the same world of things.

(But like all rules in art, throw this one out if it doesn’t serve your poem—some poems thrive on inconsistency.)

5. Choose your title strategically

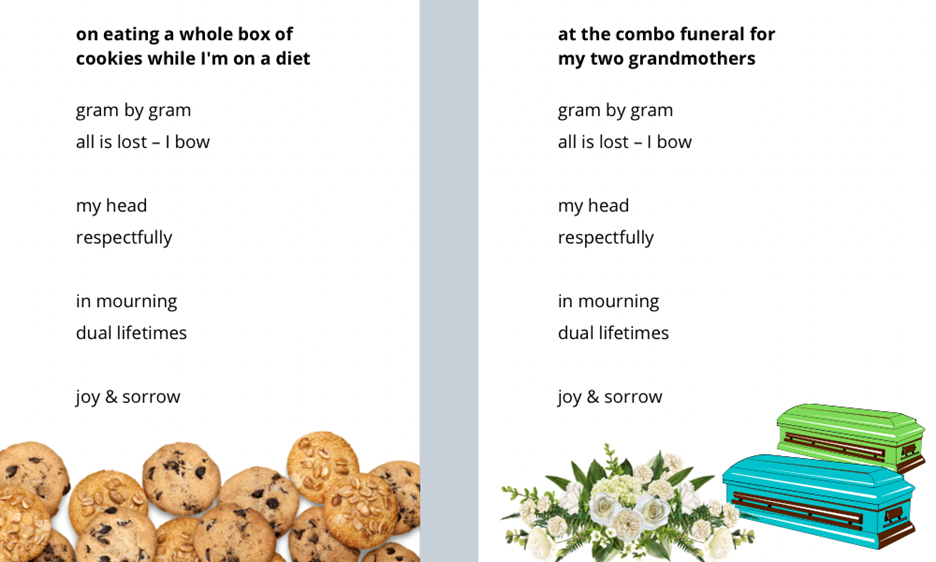

one poem, two titles—or two different poems?

Titles can constrict or free, frame or confuse, guide or abandon, elucidate or obscure. They can be heart-wrenching, or merely a utilitarian hook for the cloak that is the poem.

To determine what kind of title would best suit your poem, one consideration (of many) is whether the poem itself is more straightforward or roundabout, overall. The title can often benefit the poem by providing a balance.

For example, perhaps for your more straightforward and cheerful poem about growing lettuce, a more roundabout title could provide some bite:

I hate my mother’s hobby

—or even a touch of humor:

“You will accomplish great things.”

– my high school advisor

Equally, a more roundabout poem may be enhanced by a straightforward title. For example, this poem of mine. The body of the poem was adapted from text found in a Wikipedia article on missing persons, and as such, it’s quite roundabout. Without its very straightforward title, I would have been unable to communicate the thesis of the poem.

6. Examine Your Intentions

In the revision process, it’s super helpful to go through a checklist of sorts to examine what you’ve consciously or unconsciously chosen to do in your poem, and whether those choices align with your intentions for the poem.

Even if you feel good about your poem being its strongest and most intentional self, the process of checking can help you become more familiar with your poem, and form a stronger relationship with its thesis.

I’ve previously written a guest post for Trish about this exact topic, so do check that out. It includes a downloadable checklist I made for just this purpose.

I hope these 6 steps help you revise all those yet-unfinished poems which the world needs to read!

Upcoming Workshops

Elisabeth Blair is a Montréal-based poet and editor with an extensive background in music and the visual arts. Her poetry memoir because God loves the wasp (Unsolicited Press, August 2022) is now available for pre-order. She’s also authored two chapbooks (We He She/It from Dancing Girl Press, 2016; and without saying from Ethel Press, 2020) and published poems in a variety of journals, including Harpur Palate (forthcoming), Feminist Studies, cream city review, and Juked. She regularly leads online poetry workshops, both independently and in collaboration with the Vermont-based Burlington Writers Workshop.

Elisabeth Blair is a Montréal-based poet and editor with an extensive background in music and the visual arts. Her poetry memoir because God loves the wasp (Unsolicited Press, August 2022) is now available for pre-order. She’s also authored two chapbooks (We He She/It from Dancing Girl Press, 2016; and without saying from Ethel Press, 2020) and published poems in a variety of journals, including Harpur Palate (forthcoming), Feminist Studies, cream city review, and Juked. She regularly leads online poetry workshops, both independently and in collaboration with the Vermont-based Burlington Writers Workshop.

Discover more from Trish Hopkinson

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Categories: Guest Blog Posts, Self-taught MFA