This article was excerpted and adapted from a 3-part series on writing from the liminal mind, published through the author’s monthly poetry craft newsletter, lullabies & alarms.

In 2017 I launched a collaborative performance practice called the Improv Poetry Orchestra (IPO). It’s a simple enough set-up – a poet writes improvisatory poetry on a laptop at a desk onstage, which is projected onto a screen behind her. Musicians onstage read the writing as it’s being generated, and they improvise in response to—and in tandem with—her.

The author (lower left, at desk) writing improvised poetry live onstage in 2017 (this photo washes out the screen where the words are being projected)

It’s thrilling to participate in, and can make for exciting and engaging performances. Below is a screenshot recording (from the writer’s point of view) of an IPO performance in which I was the poet. I share this particular recording not because it’s especially stellar poetry (it isn’t) but because the process was so wonderful. A baby crying in the audience spurred the first words I wrote, which spurred the rest of the poem. The audience, musicians, and I made the piece together. (It’s worth noting that this is probably the most narrative & straightforward poem generated by the IPO—they are often (deliciously) a tad stranger.)

Improvisatory writing—and any form of creative improvisation—can be a profoundly connective process. It draws disparate people and/or ideas together (connective), and it’s centered around the act of creation (process) rather than around artistic intentions or a final product.

And unlike other skills which you must master from the ground up, you already have a lifetime of experience with improvising. Each day when you have a conversation with another person, you generate sensible, interesting statements spontaneously. Creative improvisation is similar—it just requires a little courage to be both nonsensical and unimpressive (yet occasionally amazing!), a few tools, and some practice.

Improvising doesn’t utilize one single technique. Instead, it’s akin to an artist standing before a blank canvas with an array of different tools (paintbrushes, pens, buckets, spray bottles, rubber stamps, feathers, glue, cut-up magazines, stickers, etc), and then—in real time, without planning or erasing (mostly)—making a work of art.

Photograph by Ed Schipul, usage license CC-BY-SA 2.0

Improv comedy’s famous rule-of-thumb, “Yes, and,” emphasizes the importance of:

- accepting the character or scene a colleague initiates (“Yes”), and

- adding something related but new to it (“and”).

When improvising poetry, whether alone or in a group, it’s just as handy a dictum. Whatever you write, say “yes” to it. Then let it direct the next thing you write.

With “regular” writing, you’re trying to fit things mutually together—all parts have equal potential power. With improv writing, power passes like a hot potato. Each subsequent element helps determine the element that follows, simply by paying attention to things, such as:

- the sensory situation in which you’re writing

- memories or ideas associated with a word, and the resulting stepladder of consecutive, tangential ideas and memories

- sonic similarities

- translations and transmutations—leaping from:

- a physical description to its emotional counterpart

- past to future

- place to person

- rightness to wrongness to middle-way-ness

- truth to fiction

…and so on!

If you practice noticing the many associations that orbit any given word, object, situation, idea, or memory, you’ll get more adept at quickly improvising.

Re-presenting Improvised Texts

William Carlos Williams (1883-1963) created his book Kora in Hell: Improvisations (1920) by writing improvised poetry every single night for a year.

After cutting the 365 texts down to a choice selection, his revision process involved providing commentary to go with many of the individual “improvisations.” Here’s an example—the improvisation comes first, followed by the commentary in italics:

*

XI

1

Why pretend to remember the weather two years back? Why not? Listen close then repeat after others what they have just said and win a reputation for vivacity. Oh feed upon petals of edelweiss! one dew drop, if it be from the right flower, is five years’ drink!

————-

Having once taken the plunge the situation that preceded it becomes obsolete which a moment before was alive with malignant rigidities.

*

To revise and re-present improvised texts—which might be strange and/or indecipherable, at first glance—you might consider editing, adding footnotes, endnotes, illustrations, photographs, creating a graphic presentation on the page if the poem is printed, or adding dances, gestures, and props if the poem is performed.

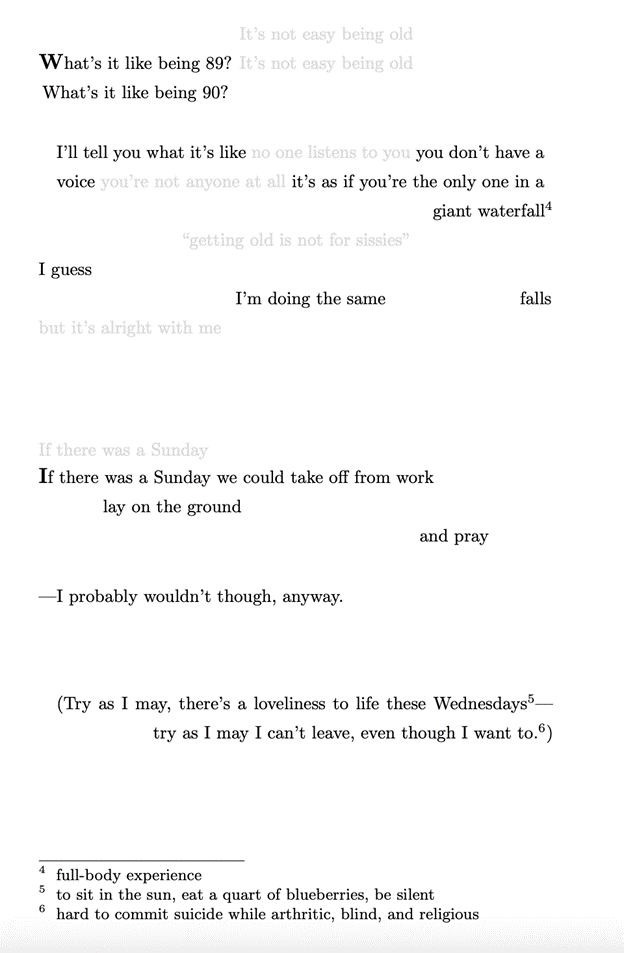

I once sang an improvised 10-minute song—essentially a sung, improv persona poem—from the point of view of a friend in the final months of her life. (As I improvised, a colleague did electronicky things to my voice in real time, and later made a video to go with the recording.) Because it was an improvisation, I mixed real memories of things she’d said together with adjacent associations.

Later, I transcribed what I’d sung, put a shape to the text, used greyed-out fonts to de-emphasize some parts, and added some footnotes. Here’s one page:

excerpt of “In the Middle of the Room,” first published in 2018 in cream city review

From start to finish, creating this piece was a deeply cathartic process for me, as I mourned the loss of my friend and attempted to honor her memory.

Writing Challenge: Guided Improvisations

If you’d like to try your hand at improvising poetry, I’ve recorded two brief, guided improvisation writing exercises which I hope will reproduce—however approximately—my own improvisation process. Grab a writing tool and listen, or use the transcription and your own stopwatch. Try to focus on the process rather than the product—and enjoy yourself!

- Poetry Improvisation Guide #1 (5:23 long)

- Poetry Improvisation Guide #2 (6:22 long)

- Transcription of both guides (PDF)

Upcoming Workshops

Please pay only what you can afford; all payments go directly to supporting my writing and teaching. If you do not have the financial resources to pay, please select the “Solidarity” ticket option.

- 5/14/22: Bridging the Strange & the Familiar: Practical Approaches for Poets

- 6/4/22–6/25/22: The Geography of the Poem (four-week session)

- 10/8/22: Poetry About a Difficult Past: One Approach

Elisabeth Blair is a Montréal-based poet and editor with an extensive background in music and the visual arts. She has been artist-in-residence at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, Wildacres, the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts, and ACRE. Her publications include forthcoming full-length poetry memoir because God loves the wasp (Unsolicited Press, August 2022), two chapbooks (We He She/It from Dancing Girl Press, 2016; and without saying from Ethel Press, 2020) and poems in a variety of journals, including Harpur Palate (forthcoming), Feminist Studies, cream city review, and Juked. She regularly leads online poetry workshops, both independently and in collaboration with the Vermont-based Burlington Writers Workshop.

Elisabeth Blair is a Montréal-based poet and editor with an extensive background in music and the visual arts. She has been artist-in-residence at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, Wildacres, the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts, and ACRE. Her publications include forthcoming full-length poetry memoir because God loves the wasp (Unsolicited Press, August 2022), two chapbooks (We He She/It from Dancing Girl Press, 2016; and without saying from Ethel Press, 2020) and poems in a variety of journals, including Harpur Palate (forthcoming), Feminist Studies, cream city review, and Juked. She regularly leads online poetry workshops, both independently and in collaboration with the Vermont-based Burlington Writers Workshop.

Discover more from Trish Hopkinson

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Categories: Guest Blog Posts, Self-taught MFA